Why does public conflict over societal risks persist in the face of compelling and widely accessible scientific evidence?

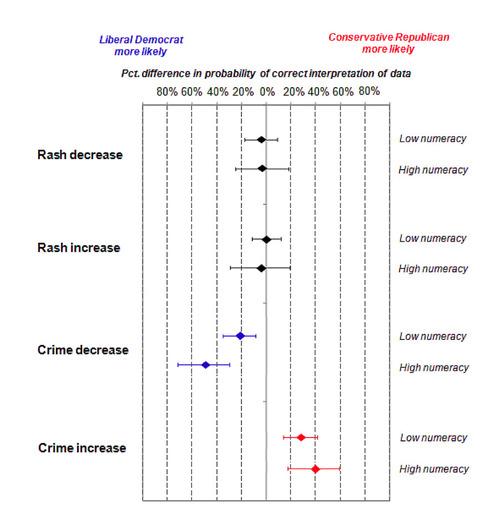

“Where reliance on low-effort heuristic reasoning suggested an inference that was affirming of their political outlooks, high Numeracy partisans selected the answer that reflected that mode of information processing—even though it generated the wrong answer. But where reliance on low-effort heuristic process suggested an inference that was threatening to their outlooks, high-Numeracy partisans used the ability that they but not their low-Numeracy counterparts possessed to make proper use of all the quantitative information presented in a manner that generated a correct, identity-affirming conclusion. This selectivity of their use of their greater capacity to draw inferences from quantitative information is what generated greater polarization among high-Numeracy partisans than low-Numeracy ones.”

“This study now joins the rank of a growing list […] that thus supports the interpretation that ideologically motivated reasoning is not a form of bounded rationality but instead a sign of how […] otherwise intelligent people use their critical faculties when they find themselves in the unenviable situation of having to choose between crediting the best available evidence or simply [choosing the answer that reinforces their identity].”

I wonder how good human brains are at thinking? Slovic et al (2013) did some research on this recently to try and understand where the breakdown was in the public’s ability to reliably interpret completely obvious scientific data. It turns out that *thinking* degrades the average person’s ability to reliably reach correct conclusions.

In the study, when questions required a single step of inference, participants’ ability to correctly answer them became worse than chance (59% wrong). Comfortingly, the most sophisticated thinkers had at least 1 bit of optimization pressure (once they were in the 90th percentile of Numeracy or above). They were able to outperform regular thinking (41% right) and random guessing (50% right) by a decent amount (75% right). However, the high-Numeracy thinkers were only able to employ this ability for questions they didn’t care about (or where the incorrect answer had been specifically rigged to threaten a belief core to the participant’s identity).

See on papers.ssrn.com