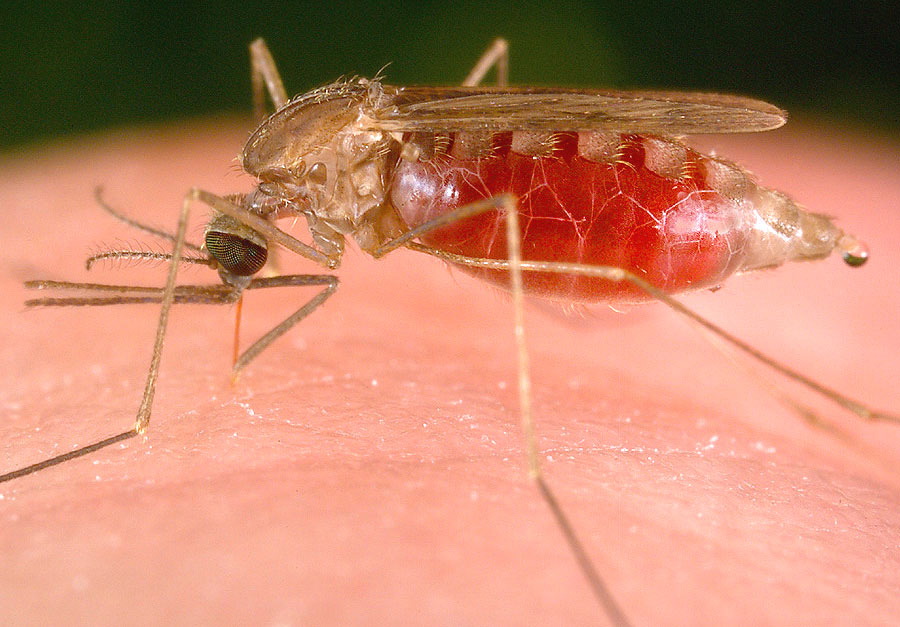

There are roughly 3,500 species of mosquitoes. But only around 100 bite humans and as few as 30-40 are responsible for the transmission of the most deadly diseases that routinely hobble the world’s poorest and most disadvantaged people. Instead of battling the estimated 219 million annual malaria cases and the resulting 600,000 deaths that occur each year in a reactionary manner by treating the sick and spending millions on wide-spread preventative measures like long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLINs), we can eliminate the disease’s only vector directly, at the source.

Specific mosquito species can be made extinct using the same sterile insect technique (SIT) that has existed for over 50 years. It has been effectively used to eliminate species before for disease prevention in humans and animals, most notably, with the screwworm and the melon fly. The technique has some subtle edges but basically reduces to releasing a large population of targeted, sterilized male insects into the wild that out-compete the wild male population for the (single) mating opportunity with their female counterparts. Repeated application of this technique can completely eliminate a wild insect population — sometimes in as little as one year.

Success in eliminating the species of mosquitoes that are the malaria vector could be followed by engineering the extinction of the vector species for dengue fever, which infects 50 to 390 million each year (causing 25,000 deaths) and also the mosquitoes that contribute to the 200,000 cases of yellow fever and the attendant 30,000 deaths they cause each year.

The short-term goals of a permanent mosquito eradication plan would prioritize and establish the species that need to be eliminated, the areas around the world where this elimination needs to be targeted first in order to succeed, and establish connections with suppliers who can provide enough sterile insects to implement these plans.

The medium-term goals would be to decimate the wild population of these species in large-scale pilot programs by releasing millions of sterile mosquitoes per day in infested areas. These marginal eradication efforts will bring with them marginal reduction in malaria and commensurate reduction in the pain, suffering, and economic/social destruction caused by this crippling disease.

The long-term goal would be the total eradication of these mosquito populations in the wild and the end of malaria, dengue fever, and yellow fever. Captive lines of all these vector species should of course be kept in labs to study and as a hedge against the unlikely futures in which unintended ecological consequences prompt us to reintroduce the eradicated species.

It’s well established by charity evaluators like GiveWell, GWWC, and AidGrade that preventing malaria using LLINs is a highly cost-competitive philanthropic intervention to save lives and promote the advancement of the world’s most disadvantaged.

If millions of dollars per year can be cost-effectively re-invested in LLIN programs over and over again in ways that outcompetes other philanthropic opportunities by several orders of magnitude, than the permanent elimination of this diseases’ transmission mechanism must be worth at least the time-discounted cost of providing that level of prevention for 5-10 years — a time horizon that charities like the “Against Malaria Foundation” fully expect to be operating within.

Additionally, there are several convergent features of this plan that make it plausibly superior to direct cash transfers to the beneficiaries. Eradication of mosquitoes that carry highly lethal diseases is a public good that cannot be easily purchased in a non-coordinated way and it’s unlikely that markets in the developing world will coordinate to deliver this innovation anytime soon. It could be argued that perhaps other more pressing needs exist that trump this public health intervention. But it also seems likely that the more pressing need in these areas is increased public health. That’s because analyses done by the Gates Foundation and other thoughtful aid organizations suggest that virtually all global problems in the developing world are insoluble so long as population growth runs beyond 3%. And somewhat paradoxically, improving health outcomes reliably convinces parents in the developing world to have smaller families since each child is that much less likely to perish before adulthood. So dramatically improving public health via targeting specific mosquito species for extinction will not only have direct effects that improve the lives of the most disadvantaged, but also have ripple-effects that make all other problems facing the most disadvantaged that much easier to solve in the future.

Government agencies have a successful track record of funding the basic research that has developed the technology required to accomplish this intervention. But none seem to have the political will necessary to implement these programs beyond pilot studies. The two large-scale roll outs of SIT in the developing world were both disrupted before they could be completed: In El Salvador, the work was terminated by the eruption of civil war and in India by hysteria induced by false accusations that the project was intended to collect data on biological warfare.

Despite expert opinion that removing several species of mosquitoes from the global ecosystem would not actually have cascading effects or negative impacts, engineering the extinction of any species simply runs counter to most funders’ sensibilities and governmental organizations political comfort zones.

If funded, even a small team of skilled non-profit administrators could marshal the research and resources to devise a tactical plan for the species and locations of these extinction campaigns.

Preliminary research suggests that as little as $1M could fund the decimation of diseases transmitting mosquitoes in an area of sub-Saharan Africa and similar amounts could improve other areas plagued by malaria and dengue fever. Once initial results are demonstrated, a redoubling of efforts could lead to full-scale extinction campaigns that permanently eliminate the malaria vectors being targeted. The timeline for this effort looks to be roughly one year for planning and insect sourcing, two years for construction and scale-up, and three to five years for field interventions in each area.

It’s possible that these costs and/or the timelines could be adversely impacted by typical planning fallacies, but it’s also possible that they could be reduced by more funding or if promising developments in “flightless female gene manipulation” continue to occur.

In 2007, a pilot project designed to eradicate malaria transmitting mosquitoes was funded by an independent donor for one million dollars. This paid to construct a mosquito rearing facility in Sudan capable of producing one million sterile males/day.

This is consistent with more detailed financial models for funding SIT rearing facilities developed by the IAEA. It appears that $1M could in fact fund the construction and operation of a small facility for creating the insects required to wage an extinction-level campaign against certain species of mosquitoes if the campaign’s directors are willing to spend over a decade on the project. A larger coalition of funders could hasten extinction of these species with as little as $10-25M in follow-on funding for each area being targeted.

12 Responses to “Engineering the Extinction of 40 Species of Mosquitoes”

May 4

Paul BohmOk I’m convinced

May 4

Ben KuhnAwesome writeup! Do you know if GiveWell is looking into this? I can’t find anything on their website.

May 4

Louie HelmI dunno. Holden?

May 4

Holden KarnofskyI’ve discussed these sort of thing before and have an impression that the Gates Foundation is interested in it. Whether we look into this sort of thing would depend on whether we select malaria control/elimination as a priority area for GiveWell Labs, a determination that will probably be made in 2015. My off-the-cuff guess is that this sort of work is being adequately explored with support from BMGF.

May 4

Paul BohmLouie: do you know about the alternate route of using wolbachia to control dengue (and potentially malaria)? there are field tests of this already. http://emph.oxfordjournals.org/content/2013/1/197.full

May 5

Luke CockerhamI’ve never understood how Douglas Adams could summarize a planet that contained death spreading mosquitoes as “Mostly Harmless.”

June 3

Christian KleineidamThe fact that those mosquitoes can live on them but not or Mars or Venus might be a clue.

May 5

Louie HelmNeat Paul! Let’s get more Wolbachia. Paper says it works for Dengue. There are early research papers explaining why it should work for malaria but it’s not as clearly possible to kill Malaria off this way. Still a huge win if you can get some reduction at all to help get things more under control.

June 9

WolfI think many people would be willing to donate for such a project if it was done using a platform like KickStarter.

July 30

Joe OwensBut their not meant to get extincted. We need them to keep the third world in check. We have screwed population up already, so not to let it get totally out of control. In fact, we need more mosquito’s that bite humans in the third world, to balance out what the egalitarians and liberals have done.

November 5

ImranShame on you Joe. You refer to human beings living in the “third world” as if they were inferior people. Wake up !!! Colonialism is over. First of all mosquitoes are not only present in poor countries, they are everywhere. Secondly mosquitoes would definitely bite you too and get you sick which proves that you as as tasty and genetically compatible to the diseases. in short it proves that you are human too (unfortunately). Mosquitoes kill over half a million people including children and babies every year.

If what you meant was what would these kids grow up to become, then my answer is poverty (unlike malaria, dengue or yellow fever) is not a disease.

It seems that the natural selection process has evolved from only the strongest and fittest survives during barbarian ages (or in nature) to a new world where the wealthy, the researchers and Labs now hold the keys to survival by producing and distributing remedies or not.

The issue though is that an infinite number of dormant viruses and diseases are still out there somewhere and burst out suddenly one by one someday. If we do not have a solution to existing and known diseases or have control on their vectors (i.e. mosquitoes) human kind might not survive the next 3 big waves.

One tiny mighty insect eradicated would clear from our path 3 important diseases at once. I say ….way to go !!!

November 26

ed mooreHow expensive can it be in the first place, and why are the dollar and cent facts not researched? Seems like it could be a science project for college students at any university worth attending.